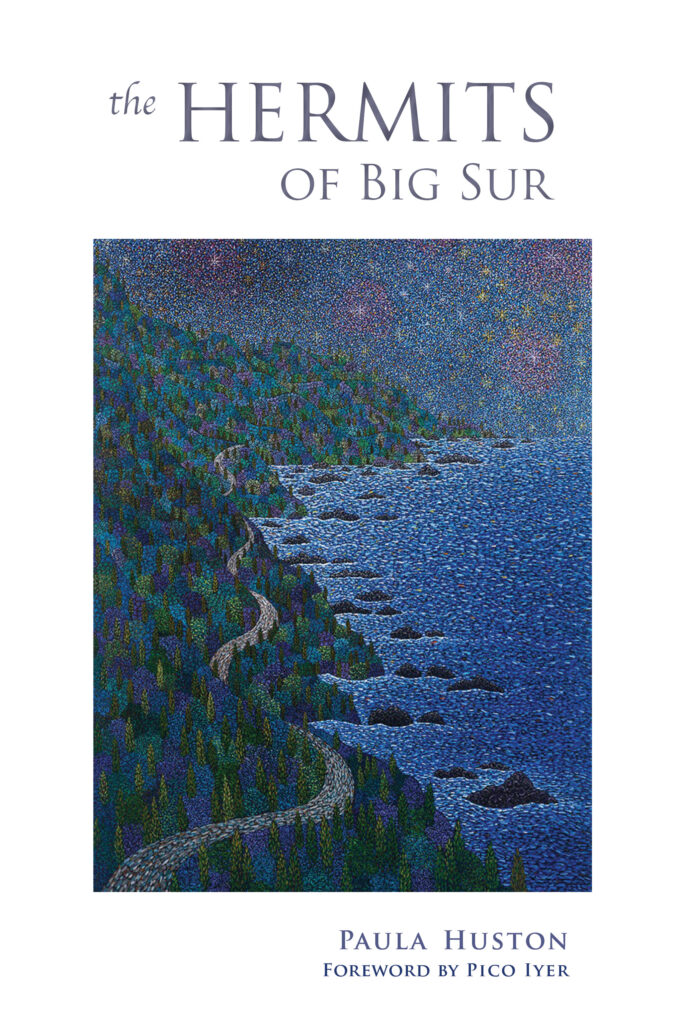

Today, I continue my ongoing series of conversations with published authors as I’m joined by Paula Huston, whose most recent book The Hermits of Big Sur is a book that thoroughly transfixed me. I’ve followed Paula’s writing for years and have even had the joy of ministering alongside her at a retreat. But this particular book took my love for her writing to an entirely new level and challenged me so deeply. As I think you’ll note in our conversation below, Paula approached the subject matter of this book with an intensely personal connection. But her encyclopedic work here is not only historically fascinating but also deeply spiritual. Believe me when I share that I’m already looking at dates to make a personal retreat at New Camaldoli Hermitage. Even if you can’t get to Big Sur or to Italy physically, this book will take you on a journey of the heart. Enjoy! Lisa

Q: Paula, congratulations on the publication of The Hermits of Big Sur. Before we turn to how much I loved your book, please briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I’m glad to do that! I’m one of those writers who began young—as soon as I learned to read, I knew I wanted to write books someday, and in fact, tackled my first novel when I was only seven (the German Shepherd star of my story looked and acted an awful lot like my 1950s TV hero, Rin Tin Tin). Later, instead of doing the obvious thing and going to college to study creative writing, I got married at nineteen and began working full-time. At twenty-four, I took a three-week leave before the birth of my first child, and that’s when I began sending out short stories to literary magazines. It wasn’t until I became a single mother of two in my early thirties that I got serious about getting a college degree. I don’t recommend this route for people on the writers’ path—I created a lot of unnecessary obstacles for myself along the way—but eventually, I arrived in the magical place I’d envisioned as a child: The Land of Published Authors. Hermits is my tenth book, written in the older—and hopefully wiser!—phase of my long and bumpy writerly journey.

Q: As you share in your book, you have a very personal relationship with New Camaldoli Hermitage. But this book is not a spiritual memoir but rather a compelling historical tome on the history of this place and some of the men and women who are part of its story. What inspired you to write the book and to choose this type of format?

I have to say that this book was not my idea! In fact, I was just starting to work on the mystery series I’d been planning for a decade when Fr. Robert Hale, who entered the first novice class at New Camaldoli in 1959 and kept careful notes for over sixty years, asked if I would help him organize and edit these for a possible “family history” dedicated to his fellow monks. I spent a moment weighing these two intriguing projects against one another—mystery or history?—but given how much I loved Fr. Robert, there was never any doubt about what to do. We agreed that he would send me batches of his notes over the next few months, and then we would put our heads together. Tragically, soon after he sent me the final pages, he suffered a fatal fall at the hermitage. The prior, Fr. Cyprian Consiglio, asked if I would continue with the project, this time as my own. Immediately, I knew I wanted to write this book as a biography—though as the life story of an institution rather than a single person—rather than simply producing a historical account of the monastery’s founding.

Q: Readers will soon discover that while this book tells a long story in great detail, you choose not to offer the facts chronologically. I can only imagine how much this decision created writing challenges! Why view the story through the prism of spiritual themes rather than strictly telling the story in order?

One thing I learned from the novel I tried to write when I was seven: readers get bored with long spells of narration (i.e., “So-and-So was born in Such-and-Such on Such-and-Such a date”) but love scenes (i.e., “So-and-So slid from the back of his sweaty horse and staggered toward the shimmering water hole”). Most readers respond far more emotionally to fiction—which employs all the compelling techniques of movie-making, minus the camera—than they do to lists of facts, especially when these are presented in unrelenting chronological order. So I knew I’d have to leap around in time. But given how much time was involved (a thousand years!) and how many characters I was dealing with, I had to find a way to pull all this together—which is why, Lisa, the “prism of spiritual themes” is such an apt way to describe the technique I finally chose.

Q: I loved the book for many reasons, but partially because I learned so much history in reading it–both about Italy and about our home state of California! What was the most interesting history lesson you learned in your writing?

I’d have to say that I was the most startled by what I discovered about early 20th century Italy, and particularly about the Church during that tragic, post-WWI era. I had no idea, for example, that the inventor of fascism and Italy’s dictator for over twenty years, Benito Mussolini, sought out and achieved an elaborate concordat with Pope Pius XI—a mutual agreement not to criticize one another as long as neither crossed certain lines. Mussolini—one of the wiliest and most ruthless politicians who ever lived, a man who despised the Church—was smart enough to know that he could not retain the loyalty of the mostly-Catholic Italian populace if he were seen as an enemy of the pope. So he put on a convincing show of piety: he had his children baptized and confirmed, he shored up the faltering Vatican bank, and he made a lot of magnanimous gestures, like allowing crucifixes to once again be hung in classrooms. This public cordiality between dictator and pope did not last long—both men were too powerful and strong-willed to put up with each other for long—but I found this little-known period of Church history utterly fascinating.

Q: Please share one or two of your favorite “characters” from New Camaldoli. What did writing about them teach you?

I had a great time writing about Fr. Thomas Matus, now the oldest monk at NCH, who came to the hermitage in 1961. In fact, along with Fr. Robert, who provided me with those precious sixty years of notes, Fr. Thomas was my most important source for the book. At eighty-plus years old, he’s one of those truly amazing people who can remember almost verbatim everything he’s ever heard or read. Though American-born, he’s completely bilingual in Italian and in fact spent much of his monastic life in Old Camaldoli, the ancient motherhouse in the Apennine mountains overlooking Tuscany. So he was able to fill in much of the back-story for me in regard to why a group of hermits would want to establish a daughter house on the wild Pacific coast of California in the late 1950s. What Fr. Thomas’s story taught me was the importance of paying attention to a call from God, no matter how confusing it might be. He went through some suffering at the beginning of his long life as a monk because he had such unusual gifts and it took so long to figure out how he was meant to use them. But he never lost faith in that original call to NCH.

The other fascinating character for me was Therese Gagnon, a French-Canadian artist who, with her artist husband, showed up at the hermitage in the early 80s, offering to teach young monks how to make ceramic pots in exchange for permission to live on-site for a while. Therese was the first woman to become part of this very male community, and thus a true pioneer; she paved the way for the countless women today who consider NCH their spiritual home. And she was so droll, so full of fun—I love listening to the heavily accented interviews I recorded with her in the year before she died at age 96. What I learned from Therese was that a woman who is brave and stubborn enough can change a whole culture; when Therese first arrived, many of the original monks were still alive, and a lot of them had been trained to fear and mistrust the company of women. She set out to change their minds, and she did! She inspired me to stick to what I believe, even if everyone around me thinks I’m nuts.

Q: You share in your Afterword some of your own experience as a Camaldolese Benedictine Oblate. Could you briefly share what it means to live as an Oblate and what writing this book has meant for this part of your spiritual journey?

I made my first visit to NCH in 1991 and was completely knocked over by what I experienced there. Aside from gawking at the horse-drawn plows of Amish farmers in Pennsylvania, I’d never before seen people living a totally alternative lifestyle in order to better practice their faith. This really impressed me. Most of the Christians I knew (I’d considered myself an atheist for a number of years by then), were almost indistinguishable from their non-believing neighbors—but here were these monks, and I couldn’t ignore what they were stirring in me in regard to my own spiritual life. It wasn’t long after I met them that I began going to RCIA classes and became a member of the Church—something I can’t imagine myself doing without the example set for me by the hermitage. Eight years later, I became an oblate, which means a non-monastic member of the community. The word “lay” doesn’t quite fit here, as there are priests and sisters and pastors who become oblates too. The oblate journey has been a long one; there’s so much to reassess, so much to let go of, so much to incorporate. Was I trying to maintain a career that demanded everything from me? (I was). Was I completely exhausted and stressed out by my work, no matter how satisfying I found it? (For sure). Did I even have time to set aside for daily prayer, lectio divina, meditation? (I did not). Did I perhaps need to think about a career change? (I did—which led to my leaving teaching to become a full-time writer). As Eugene Peterson once described his own spiritual life, being an oblate has proven to be a “long obedience in the same direction” that has had major implications for who I am still becoming.

Q: For readers–like me–who emerge from reading this book and would like to know more about the Hermitage, what would you recommend?

The best source of information about New Camaldoli Hermitage is their wonderful website, www.contemplation.com. There, you’ll find the history of the community, homilies offered by various monks, photographs of the stunningly beautiful Big Sur setting, a guest room reservation page—and also a whole section on oblates, including lists of recommended books.

Q: Are there any additional thoughts or comments you would like to share with our readers?

Yes, thank you for asking. I really do believe that some people are strongly called to the contemplative path. But because they have never visited a monastery or know any monks, they don’t realize that this confusing ache inside is really an arrow pointing toward a certain kind of life—an intentional way of living that ultimately frees them from the impediments to solitude, silence, and deep prayer that they don’t even know they’ve placed in their own way. The beautiful thing about the oblate life is that it can be lived under any circumstances—as a spouse, a parent, or a single person. The Camaldolese charism (which means, “special gift for the world”) is three-fold—community, solitude, and outreach—and the monks have a beautiful way of speaking about their common life: they call it “the privilege of love.” That’s an ethos that can transform any community.

For More Information:

- Paula Huston

- New Camaldoli Hermitage

- The Hermits of Big Sur – Liturgical Press, Amazon